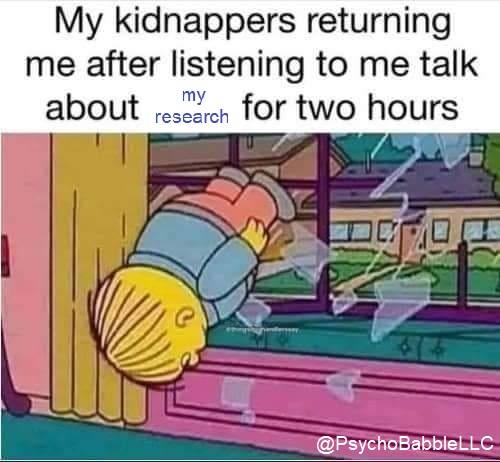

This may not come as a surprise, but researchers like talking about their research. It’s probably because we spend a lot of time doing it, and because we think it is important. At their cores, scientists want to improve the lives of others, so of course we want to share what we know!

When I tell people that I study stress, there’s a 90% chance that someone will say “you should do a case study on ME!” and I smile politely like it’s the first time I’ve heard the joke. But, there is a nugget of truth in there. Who doesn’t suffer because of the stress in their lives? Our society practically breeds it.

I could write a book about stress (in fact, kind of did it with a dissertation!) but I’m happy to share some “fun facts” that I learned while doing stress research:

The stresses on your mind create changes in your body

You can actually feel some of those changes, the ones dictated by the Sympathetic Nervous System. In “fight or flight” fashion, one may feel flushed, sweaty, the heart pounding, the whole bit. There is a second, more prolonged response happening that we can’t feel, but involves the hormone cortisol. Together they form a coordinated system that is identical whether we are in a survival situation (think: being chased by a lion) or just a psychologically stressful one (think: being in a job interview that is not going well). There is a well-studied and direct physiological pathway between stress and your health. It’s real. There are entire domains of science built around it (ex. psychoneuroendocrinology, psychoneuroimmunology).

How you react emotionally to stress matters

We discovered this by watching the faces of people while in the midst of a psychosocial stressor. Using Ekman’s Facial Action Coding System, we linked those responses to sympathetic nervous system and hormonal responses. For men, getting angry predicted a more extreme stress response than for those that didn’t. But anger is just one possible reaction to stress. I’ve seen people cry, show contempt, giggle uncontrollably, and even vomit in the face of psychological stress. Some responses may be more health-promoting than others, so we really should be thinking more about emotion-based coping.

Having a negative body image can be chronically stressful

In a series of studies with collaborators, we found people with high levels of shame and poor body esteem had more extreme stress responses. This is especially alarming given the high rates of poor body image that we see in young people (that research is nicely summarized here). It should be noted that although a lot of this research focuses heavily on the female experience, males are by no means immune from body concerns. When faced with body ideals that are impossible to attain and a relentlessly-visual social media culture, is anyone really surprised?

My biggest takeaway from this work is that I can make some conscious decisions about what I let stress me out, and what I can let fall to the wayside. Holiday shopping has to go this year, and that’s that.